ChildFund India has been working tirelessly to improve the lives of vulnerable children and their families through holistic development programmes. With a strong focus on health, nutrition, education, and child protection, the organisation is deeply committed to ensuring every child not only survives but thrives, especially during the critical first 1,000 days of life.

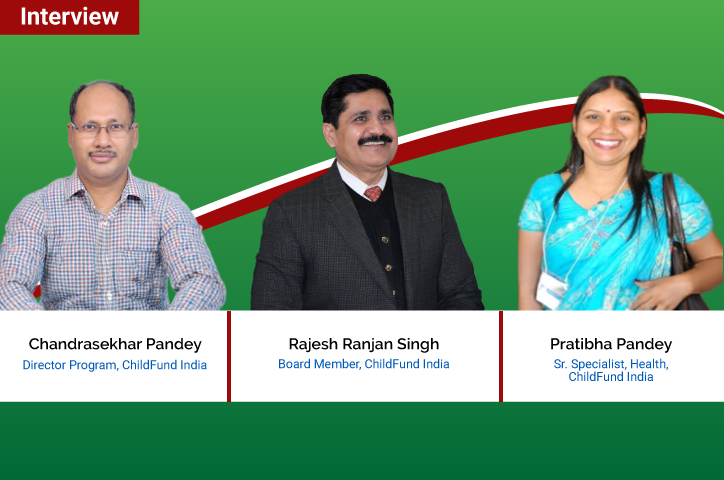

In this interview with TheCSRUniverse, Chandrasekhar Pandey (Director Program), Rajesh Ranjan Singh (Board Member), and Pratibha Pandey (Sr. Specialist, Health) from ChildFund India share valuable insights into the importance of early childhood nutrition, the impact of grassroots interventions, and scalable community-led models like Mentor Mothers and PD+. They also discuss key policy and community shifts needed to combat malnutrition and strengthen WASH in rural India.

Scroll down to read the full interview:

Q. Why are the first 1,000 days, from conception to a child’s second birthday, considered the most critical for physical growth and cognitive development?

A. The first 1,000 days, from conception to a child’s second birthday, are considered the most critical window for physical growth and cognitive development because this period lays the foundation for a child's lifelong health, learning, and well-being. In general, a child’s weight becomes 2 times in the first 6 months, 3 times by the first birthday, and 4 times bythe second birthday, which never happens in period of life. During this period, a child’s brain develops faster than at any other time in life, shaping their ability to learn, behave, and stay healthy in the future.In India, where childhood malnutrition and stunting continue to be major public health concerns, investing in the health and nutrition of mothers and young children during this phase is vital. During this period, 80% of brain development takes place, shaping the child’s ability to think, learn, and interact with the world. ChildFund India recognizes the critical importance of this window in a child’s life and works to ensure that each child receives the right care and nutrition from the start. Through targeted interventions, such as antenatal care for mothers, exclusive breastfeeding, timely complementary feeding, micronutrient support, and growth monitoring, ChildFund supports the healthy development of every child. The organization also works closely with caregivers, equipping them with knowledge and skills to nurture their child’s physical and mental well-being.

Q. Could you share examples of how timely intervention during this period has led to measurable improvements in child health?

A. Yes, when the right support is given during the first 1,000 days (from pregnancy to a child’s second birthday), it can bring big improvements in a child’s health.

- For example, in some villages where ChildFund India works, pregnant women were given regular health check-ups, iron tablets, and nutrition counselling. They also received support from community health workers and Mentor Mothers who helped them with breastfeeding and feeding advice after the baby was born. As a result, babies were born with healthier weights (more than 2500 grams) and grew better in their first year.

- Another example is AWWs, and ASHA and mothers’ groups were trained to prepare nutrient-dense ragi porridge with locally available ingredients like jaggery and groundnuts, enhancing both the taste and nutritional value. As a result, families began to adopt these improved recipes, contributing to reduced anaemia levels and better growth indicators in young children.

- In the MACHAN project, when mothers were supported to breastfeed within the first hour of birth and give only breastmilk for the first six months, children had fewer illnesses like diarrhoea and recovered early showed better weight gain.

- Another successful integration was the promotion of nutrition gardens, which have been part of rural households for generations. These gardens improved household food diversity and helped meet the daily nutritional needs of children and mothers without relying solely on market access.

- Cultural ceremonies like Annaprasan (the child’s first solid meal) were transformed into awareness events where health workers shared information on timely complementary feeding at 6 months, handwashing, and food safety.

Q. How does Positive Deviance Plus (PD+) help identify and replicate successful child-nourishment behaviors within resource-poor communities?

A. Positive Deviance Plus (PD+) is a community-driven approach that helps identify successful child-nourishment behaviours practiced by families who are nourished and healthy despite facing the same challenges as others in resource-poor settings. In the context of malnutrition in rural India, PD+ enables communities to discover local solutions from within, rather than depending on external interventions. It focuses on identifying “positive deviants”—mothers or caregivers who have well-nourished children despite poverty, limited food availability, or poor sanitation.

The PD+ process begins with growth promotion monitoring and participatory assessments to identify well-nourished children from economically similar backgrounds. Teams then study the caregiving, feeding, hygiene, and health-seeking behaviours of these families. Common successful practices include frequent feeding using small portions, handwashing before feeding, and the use of locally available and seasonal foods like ragi, moringa leaves, lentils, and fermented foods that enhance nutrient absorption. These findings are then replicated through community-led behaviour change activities, such as health sessions (nutrition camps), mother group meetings, cooking demonstrations, and home visits by trained volunteers or frontline workers.

PD+ empowers communities to believe that solutions already exist among them, fostering ownership, sustainability, and cultural acceptance. In ChildFund India’s MACHAN project, PD+ has been instrumental in transforming nutrition outcomes by building on existing knowledge and promoting low-cost, high-impact behaviours that are sustainable even after external support ends. The approach not only improves child health but also strengthens community solidarity, maternal confidence, and long-term resilience.

Q. Who are “Mentor Mothers,” and what role do they play in transforming maternal and child health outcomes?

A. Mentor Mothers are experienced mothers from the community who are trained to support other women, especially pregnant women and new mothers, by sharing knowledge, guidance, and encouragement. They play a very important role in improving the health and nutrition of both mothers and young children.

Because Mentor Mothers come from the same community, they understand local customs, language, and challenges. This makes it easier for other women to trust them and follow their advice. Mentor Mothers are trained in pregnancy care, breastfeeding, child nutrition, hygiene, and early childhood development. They visit mothers at home, lead small group meetings, and demonstrate healthy practices like how to prepare nutritious meals using local foods.

In programs like ChildFund India’s nutrition project, Mentor Mothers have helped reduce malnutrition, increase safe births, and improve practices like exclusive breastfeeding and timely complementary feeding. By guiding other mothers with simple, practical tips and emotional support, they help build healthier families and stronger communities.

Q. How has ChildFund India helped build leadership among these women to drive behaviour change at the grassroots level?

A. ChildFund India helps women become leaders in their own communities by training them as Mentor Mothers, Lead Mothers, and active members of Mahila Arogya Samitis (MAS). These are women who live in the same villages or slums and understand the local language, customs, and challenges. ChildFund trains them on mother and child health, nutrition, hygiene, mental well-being, and how to talk with and support other women. They also learn how to speak confidently, solve problems, and keep simple records.

Once trained, they lead mother group meetings, nutrition sessions, home visits, and awareness campaigns. They promote healthy behaviours like exclusive breastfeeding, complementary feeding with local foods, handwashing, antenatal check-ups, and emotional support for mothers. As part of the Mahila Arogya Samitis, which are community women’s groups under the National Urban Health Mission, these women play a crucial role in planning and monitoring health services at the local level. ChildFund supports their participation in Village Health and Nutrition Days and helps them work alongside ASHA workers, Anganwadi workers, and ANMs to ensure better service delivery and stronger community engagement.

Through this approach, ChildFund India not only improves health and nutrition outcomes for women and children but also empowers women to become decision-makers and health champions in their own communities. Their active involvement in MAS and other platforms helps them raise local health issues, advocate for services, and support others, making them powerful agents of lasting change at the grassroots level.

Q. What lessons have emerged from the Mentor Mother model that can be scaled or adapted nationally?

A. The Mentor Mother model has shown that when local women are trained and supported, they can become powerful health guides in their communities. One big lesson is that peer-to-peer learning works best—mothers feel more comfortable learning from someone like them who speaks their language and understands their problems. Mentor Mothers help increase trust in health messages and make it easier for families to follow good practices like exclusive breastfeeding, healthy eating, and regular health checkups. This model has also helped reduce malnutrition and improve child growth in many rural and urban areas.

Another important lesson is that building leadership among women improves more than just health—it also empowers women, builds their confidence, and strengthens community systems. Mentor Mothers are often included in Mahila Arogya Samitis, and they work closely with ASHAs and Anganwadi workers, helping to make government services work better. This approach can be scaled nationally by training local women in every village or slum, giving them regular support, and linking them with health workers. It is low-cost, community-based, and helps bring long-term behaviour change from within.

This model proves that real change starts at the grassroots level, and that every woman, when empowered, can become a leader in improving the health and future of children across India

Q. What policy or community-level shifts do you believe are most urgently needed to eradicate malnutrition in India within this decade?

A. Malnutrition is a big problem in India, affecting many children and mothers, especially in poor and rural areas. To end malnutrition within this decade, India needs urgent changes in both government policies and community actions.

At the policy level

India must improve the reach and quality of nutrition programs like ICDS and Poshan Abhiyaan. Malnutrition is linked not just to food but also to health, sanitation, education, and social protection. Hence, nutrition needs to be integrated into all related sectors. Health programs must focus on maternal nutrition and infection prevention. Sanitation programs should ensure safe drinking water, toilets, and hygiene practices. Education policies should include nutrition awareness and school meal programs.

Lastly, increased budget allocation and efficient use of funds for nutrition programs are essential to sustain and expand these efforts.

Community-Level Shifts

At the community level, knowledge and empowerment are key. Many mothers and families lack the right information or support for proper nutrition. Community programs should focus on educating caregivers with simple, clear messages about healthy pregnancy, breastfeeding, feeding children, hygiene, and when to seek health care.

Women from the community, such as Mentor Mothers and Lead Mothers, can lead these efforts. They provide peer support through home visits and mother group meetings, making it easier for families to understand and adopt good practices.

Community platforms like Anganwadi centres, Mahila Arogya Samitis (women’s health groups), Village Health and Nutrition Days (VHNDs) should be strengthened. These groups can provide services, spread awareness, and encourage healthy behaviours.

Another important shift is to engage men and other family members in nutrition efforts. Fathers, grandmothers, and elders play a big role in decisions about food and health. Including them helps create a supportive environment for mothers and children.

Technology and innovation can also support these efforts. Mobile phones can be used to send health messages and reminders. Digital tools can track child growth and service delivery to ensure no one is missed.

Q. What is the most pressing WASH-related challenges in rural India today, and how is ChildFund India addressing them?

A. In rural India, many people still face big problems related to water, sanitation, and hygiene (WASH). According to the National Family Health Survey (NFHS-5), about 19% of rural households still do not use any toilet facility, and only 58.2 % have drinking water facilities within their premises. Poor hygiene practices are also widespread — nearly 40% of people in villages do not regularly wash their hands with soap after using the toilet or before meals. Every day, around 300 children under the age of five die in India due to diarrhoea, which is often caused by unsafe water and poor sanitation.

To solve these issues, ChildFund India started a program called SWASH++ (School, Water, Sanitation, and Hygiene) in government schools across 7 states, helping around 15,000 children. We also run handwashing campaigns using posters and fun activities in class. Girls received menstrual hygiene education, and all children were given life skills training to help them understand hygiene, nutrition, and body changes. ChildFund India plans to scale such initiatives and integrate climate-sustainable WASH models, ensuring children have access to safe and sustainable WASH services across more districts. The program supports the national goal of Swachh Bharat Abhiyan and connects schools with government health programs.

Q. Can you shed light on how integrating WASH and nutrition programs can lead to better health outcomes?

A. Clean water, proper sanitation, and hygiene are as important as good food. Even if a child is eating enough, dirty water and poor hygiene can cause diseases like diarrhoea, which stops the body from absorbing nutrients. According to UNICEF, 45% of child deaths from undernutrition are linked to poor WASH conditions. Diarrhoea alone kills around 300 children under five every day in India, mostly due to unsafe water and lack of toilets.

When WASH and nutrition work together, they protect the health of children. Clean drinking water reduces the chances of waterborne diseases. Handwashing with soap can reduce diarrhoea cases by up to 47%, as reported by the World Bank. This means fewer children get sick and more of the food they eat is absorbed by their bodies, helping them grow stronger. Studies also show that children living in clean environments are 33% less likely to be stunted, a sign of chronic malnutrition.

Programs that combine WASH and nutrition also teach families to follow safe habits like breastfeeding, using clean water for cooking, washing hands before eating, and keeping food and utensils clean. This is especially important for pregnant women and young children. The Government of India’s Poshan Abhiyaan recognizes the importance of WASH and nutrition together and has made hygiene behaviour a key part of its plan to reduce malnutrition. Under this mission, Community Health Workers (ASHAs and Anganwadi workers) are trained to promote both nutrition and hygiene in villages. In short, when WASH and nutrition are combined, they break the cycle of disease and malnutrition.

Q. Could you provide examples where traditional practices, when aligned with modern nutrition science, led to positive results in community-based programs?

A. In many parts of India, traditional food and health practices have been passed down for generations. These practices often use local, seasonal, and natural ingredients that are both affordable and healthy. When such traditional knowledge is combined with modern nutrition science in community programs, the results are powerful. People understand and accept messages better when culturally appropriate traditional practices are encouraged and become more sustainable.

One good example is the use of traditional recipes with locally available millets. ChildFund India also supported the development and distribution of local recipe booklets, written in simple language, using seasonal and locally available food items. In states like Odisha, Rajasthan, and Karnataka, nutrition programs have promoted the consumption of millets like ragi (finger millet), bajra (pearl millet), and jowar (sorghum), which were once common in traditional diets. These grains are rich in iron, calcium, and fibre. Modern science supports their role in preventing malnutrition, especially iron-deficiency anaemia in women and children. ChildFund India, through its nutrition programs, has encouraged mothers to prepare traditional millet-based dishes like ragi porridge and bajra roti for children and pregnant women. This helped improve iron intake and reduce cases of anaemia in many villages.

Another example is the use of traditional complementary feeding practices for infants. In many rural areas, mothers feed babies mashed khichdi (a soft mixture of rice, lentils, and vegetables), banana, or cooked and mashed sweet potatoes. These foods are nutritious and easy to digest. Modern nutrition science supports these practices but adds guidance, like adding a spoonful of oil or ghee to increase energy content or including green leafy vegetables for added vitamins. In ChildFund’s nutrition projects, Mentor mothers and Mahila Arogya Samities trained mothers to improve traditional baby foods using these small, science-backed changes.

In tribal communities of Madhya Pradesh and Chhattisgarh, traditional foods like mahua flowers, amaranth, bamboo shoots, and jackfruit are being revalued for their nutritional benefits. With support from Mentor mothers and Poshan Mitras, Mothers learned how to prepare these foods in more hygienic and nutrient-preserving ways.

.jpg)