Across the globe, creating truly inclusive societies faces significant challenges, particularly in underserved communities where poverty and limited access to services disproportionately impact people with disabilities or PwDs. In India's Yadgir and Raichur districts, however, a powerful solution is taking shape. The Association of People with Disability (APD) is leading the Life Cycle Approach - LCA, an innovative and comprehensive model that's fundamentally transforming how disability support is delivered.

With crucial funding from the Azim Premji Foundation in Yadgir and the SBI Foundation in Raichur, this ambitious project aims to reach 27,500 PwDs and Children with Disabilities (CwDs). The LCA's core strength lies in its ability to provide tailored, community-rooted, and rights-based interventions that support individuals throughout their entire lives. This ensures not just immediate relief, but a lasting environment where dignity, entitlements, and opportunities are genuinely accessible to everyone.

The Genesis and Core Design of a Holistic Vision

The choice of location for this profound initiative was deliberate. Yadgir and Raichur are not just geographically remote; they consistently rank among Karnataka’s lowest in terms of human development, as per UNDP reports. Poverty is endemic, and access to healthcare and education is severely limited. For PwDs, particularly women and girls, discrimination is layered and lifelong, often resulting in invisibility and ignorance regarding their rights and available services. Yadgir is one of India's officially designated Aspirational Districts, recognized for its urgent developmental needs and untapped potential, struggling with a low literacy rate and a widespread absence of quality, inclusive service delivery. Children in Yadgir face particularly harsh realities, with prevalent malnutrition and challenging climatic conditions marked by extreme temperatures and poor rainfall, making healthy and safe growth difficult for those with health vulnerabilities or disabilities. Raichur, a rural backward district in North Karnataka, also faces significant challenges in health, education, and livelihood indicators.

"In these communities, disability often meant invisibility," says Dr. N. S. Senthil Kumar, the lead architect of the program and CEO of APD India. "Families were unaware of services, stigma ran deep, and there was no systemic support. We wanted to change that—from the inside out.”

"In these communities, disability often meant invisibility," says Dr. N. S. Senthil Kumar, the lead architect of the program and CEO of APD India. "Families were unaware of services, stigma ran deep, and there was no systemic support. We wanted to change that—from the inside out.”

This strategic approach didn't emerge in a vacuum. It was built on the success of a robust pilot initiative in the Chitradurga block of Chitradurga district, Karnataka. Over a period of three years, APD successfully reached and mainstreamed approximately 2,200 Persons with Disabilities (PwDs) in that area. This pilot initiative was a significant success for APD. In the third year, the project was formally handed over to the local government and the Federation of PwDs and Caretakers, establishing a powerful precedent for continuity and local ownership. These crucial learnings from the pilot laid the groundwork for the expansive current phase in Yadgir and Raichur, proving that a rights-based, community-rooted alternative to piecemeal service delivery was not only necessary but achievable.

The design thinking behind the LCA model is inherent in its structured and comprehensive nature. It is described as a "systems-driven approach to disability inclusion" and a "rights-based, community-rooted alternative to piecemeal service delivery." The approach ensures the delivery of tailored services to various age groups among PwDs, guiding them along a developmental path aligned with specific timelines to achieve better outcomes. This approach is not only holistic but also cost-effective when compared to implementing standalone projects. It integrates all of APD’s existing programs within the regions of Yadgir and Raichur to leverage collective strengths and deliver services efficiently through both internal coordination and external referrals. The core of its design is a community-based rehabilitation model, which brings services directly to the people, complemented by a transdisciplinary approach and community-based rehab workers—bringing together expertise from various fields to address the full spectrum of needs.

A Phased Implementation to Drive Systemic Change

The implementation of the LCA project spans three years: for Yadgir, from June 2022 to May 2025, and for Raichur, from October 2022 to September 2025. The funding model is intrinsically linked to progress. For LCA Raichur, a three-year proposal was submitted and approved by the SBI Foundation under the CSR grant. For LCA Yadgir, a similar three-year proposal was submitted and approved by the Azim Premji Foundation. For both, the budget is sanctioned and released on a quarterly basis, contingent on the progress achieved.

The project phases were distinct and strategic, marked by clear milestones:

- Year One (Foundation Laying): The initial year primarily focused on the recruitment of human resources, establishment of project offices, building networks and collaborations with government departments, identification and profiling of PwDs, conducting assessments, and sensitization and capacity-building of various stakeholders. During this period, the team also began delivering essential services to PwDs.

- Years Two and Three (Intensive Service Delivery and Sustainability): These subsequent years emphasized scaled-up service delivery, the systematic development of a supportive ecosystem around PwDs, and robust strategies to ensure the long-term sustainability of the initiative.

To ensure accountability and effectiveness, progress assessments were conducted every six months by the internal team to track changes in the condition and inclusion of PwDs. In addition, external evaluations were carried out by expert consultants appointed by donors to provide impartial validation of the project's impact.

Building Disability Inclusion into Rural Development Programs: The LCA Model in Depth

The LCA model treats inclusion not as a one-time intervention but as a continuous journey, supporting PwDs across four interconnected life stages: early childhood, school-age, working age, and old age. Each phase is marked by targeted services—ranging from home-based physiotherapy, inclusive education, assistive devices, and skill development to access to entitlements and livelihood support. The rehabilitation strategy is broad and inclusive; it goes beyond physical care, encompassing social inclusion, education, and economic empowerment.

The LCA model treats inclusion not as a one-time intervention but as a continuous journey, supporting PwDs across four interconnected life stages: early childhood, school-age, working age, and old age. Each phase is marked by targeted services—ranging from home-based physiotherapy, inclusive education, assistive devices, and skill development to access to entitlements and livelihood support. The rehabilitation strategy is broad and inclusive; it goes beyond physical care, encompassing social inclusion, education, and economic empowerment.

"It works because it’s deeply rooted in the local context," says Dr. N. S. Senthil Kumar. "We’ve built transdisciplinary teams from the panchayat to the district level. Many of our Community Resource Persons (CRPs) are parents or siblings of children with disabilities. That changes the game."

The model's most powerful feature is its ecosystem approach, which is central to building disability inclusion into rural development programs. It integrates a wide spectrum of actors, creating a robust, community-driven support system that places persons with disabilities at the center while mobilizing every layer of society to support them.

- Community Engagement: At the grassroots, APD works closely with ASHA (Accredited Social Health Activist) workers and Anganwadi workers, who serve as the first line of outreach and early intervention. They are crucial in identifying and supporting children and adults with disabilities, ensuring timely care and referral.

- Health System Integration: The health system forms a vital backbone, with over 48 Primary Health Centres (PHCs), 7 Taluk Hospitals, and 7 Rashtriya Bal Swasthya Karyakram (RBSK) teams actively involved in screening, treatment, and rehabilitation services. These medical units work in synergy with Village and Mandal Rehabilitation Workers (URW, VRWs and MRWs) to extend rehabilitation services directly into urban and rural communities. In Yadgir, 60 Community-Based Rehabilitation (CBR) centers and 6 main centers have been established and operationalized.

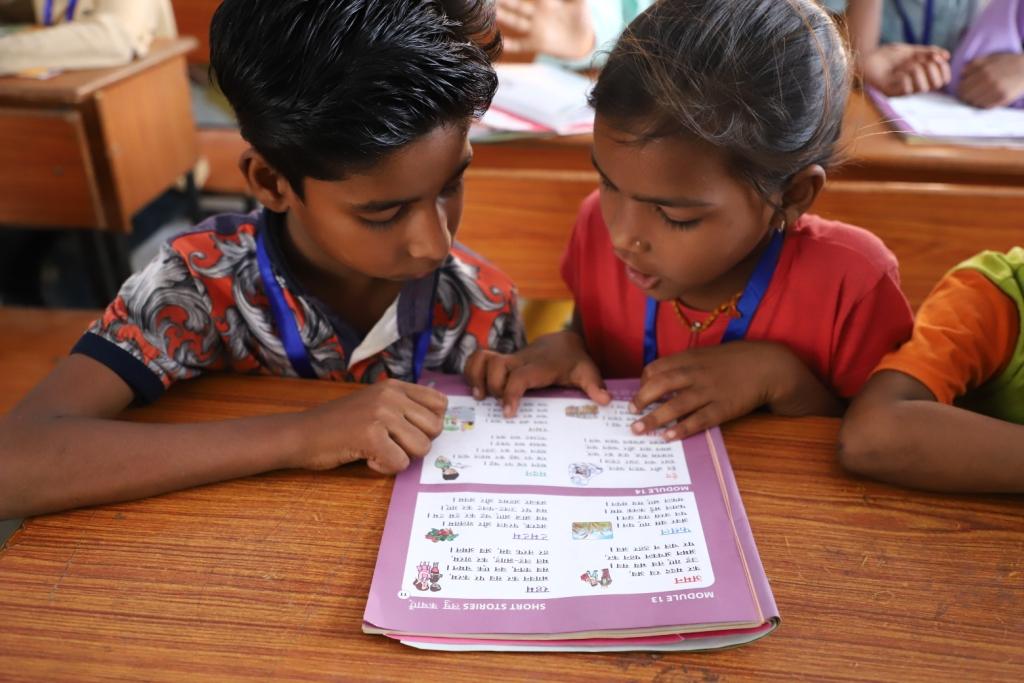

- Inclusive Education: Education is another cornerstone. Schools across the districts are being transformed into inclusive learning environments, supported by BRC/BIERT (Block Resource Center/Block Inclusive Education Resource Teacher) teams, inclusive education specialists, Deaf role models, and skilled teachers. These institutions don’t just educate—they advocate, include, and uplift.

- Livelihood & Empowerment: Youth with Disabilities are identified and screened through camps, then connected to various skills training programs, including upskilling, and enrolled for job placement to ensure they reduce dependence and live with dignity in society.

- Governance & Local Ownership: At the governance level, a tiered structure of representation and accountability is being created. Each of the six taluks will have its own federation, bringing together Disabled People’s Organizations (DPOs), carers' groups, and task forces. At the grassroots, Panchayat/Ward-level DPOs and community groups—including teachers, Self-Help Groups (SHGs), and parents—serve as local champions for inclusion. These local groups are empowered to identify needs, monitor services, and mobilize resources. At the apex, a district-level federation serves as the collective voice of the disability community, advocating for rights and influencing policy. An example of advocacy includes securing Psychiatrist doctors and health camps. By sharing responsibility across institutions and empowering local actors, APD is not only building services—they are building ownership, sustainability, and a true culture of inclusion.

Impact on the Ground: Tangible Achievements and Outcomes

The quantifiable and deeply personal impacts of the LCA model are evident. The selection of beneficiaries for the project was guided by a participatory and inclusive approach, spanning age groups from pediatric to geriatric. The process began with community-level mapping and door-to-door surveys, conducted in partnership with ASHA workers, Anganwadi staff, URW/VRW/MRD, and Panchayat leaders. Special attention was given to identifying PwDs across all age groups, especially those previously unreached or excluded from government schemes and services. The LCA helped ensure individuals were identified and supported at every stage—from early childhood intervention to adult rehabilitation and social inclusion.

Extensive Reach: To date, 26,933 beneficiaries (Yadgir: 21,650 and Raichur: 5,283) have been identified and availed various services. This includes direct beneficiaries who received rehabilitation services, assistive devices, educational support, and livelihood opportunities, awareness and training, as well as indirect beneficiaries such as family members, carers, and community stakeholders, who have been trained, sensitized, and empowered as part of the ecosystem. The project is already on track to meet its goal to cover 27,500 PwDs and CwDs.

Early Childhood Development: More than 700 children with disabilities have been identified and supported through home-based physiotherapy and inclusive education efforts. In Yadgir, 1,476 children aged 0-8 years accessed Early Intervention services, with 317 out of 536 children aged 3–6 years enrolled in Anganwadi centers. 71% of mothers (1,070 out of 1,450) in Yadgir were trained as “mothers as therapists,” actively contributing to their children's rehabilitation and well-being through 37 rehabilitation initiatives. In Raichur, 343 children (ages 0–8) received EI services, with 100% enrollment in Anganwadi centres, and 323 mothers were trained as Early Interventionists, showing improved communication and developmental engagement.

Assistive Devices: A total of over 380 assistive devices (like wheelchairs, walkers, and hearing aids) have been distributed to enable greater independence. Specifically, 1,434 PwDs in Yadgir and 297 in Raichur received mobility aids and appliances, with 90% reporting improved functional ability. The program successfully integrated Assistive and Adaptive Technology (AAT) to promote independence among 1,153 PwD beneficiaries in Yadgir.

Inclusive Education: In Yadgir, 4,025 Children with Disabilities (CwDs) were enrolled in schools, achieving an 80% retention rate. 302 out of 664 (45%) government schools were transformed into inclusive learning environments. The remaining 22% of CwDs receive home-based education due to the severity of their disabilities. In Raichur, 822 children with special needs supported in education, achieving 80% retention in mainstream schools, while 20% receiving home-based educational services.

Livelihoods and Empowerment: 60+ persons with disabilities have received seed funding and business mentoring, creating pathways to sustainable livelihoods. In Raichur, 200 youth were placed in jobs, 50 supported in self-employment, and 124 linked with MGNREGA job cards. In Yadgir, 13,562 PwDs accessed various social security schemes, and overall, 9,720 beneficiaries gained access to various social security schemes. Over 45,000 rehabilitation services have been delivered to individuals in Raichur.

Livelihoods and Empowerment: 60+ persons with disabilities have received seed funding and business mentoring, creating pathways to sustainable livelihoods. In Raichur, 200 youth were placed in jobs, 50 supported in self-employment, and 124 linked with MGNREGA job cards. In Yadgir, 13,562 PwDs accessed various social security schemes, and overall, 9,720 beneficiaries gained access to various social security schemes. Over 45,000 rehabilitation services have been delivered to individuals in Raichur.

Community Empowerment and Gender Inclusion: Over 200 caregivers, mostly women, are now part of trained and active Self-Help Groups (SHGs) that offer peer support and advocate for disability rights. Due to the LCA project, 45% of beneficiaries are female, which is in close alignment with the census percentage. The formation of 132 SHGs (112 in Yadgir and 18 local Federations in Raichur) has empowered mostly female members, promoting social, economic, and cultural inclusion. Special attention is also being paid to persons with psychosocial disabilities, with 639 individuals in Yadgir and 234 in Raichur receiving counseling and medical support.

Capacity Building: A total of 20,918 various stakeholders have had their capacities built, fostering a more inclusive environment. In Raichur alone, 7,600 stakeholders were trained on disability rights and available services.

Driving Inclusion Through Data and Overcoming Hurdles

A key strength of this project lies in its robust and multi-layered monitoring system, designed not only to track progress but to adapt, improve, and sustain impact over time. Every beneficiary is registered in a digital tracking system, the Goonjan app, assigned a unique ID that captures their journey across every service—be it therapy, education, skill training, or livelihood support, DPOs or SSS. This centralized platform allows for real-time updates and accountability.

"Yes, we are able to identify learning, gaps and work on it. We are able to track outputs and outcomes and impact of the project based on the impact indicators," notes the APD team. To ensure meaningful progress, periodic assessments are conducted weekly, monthly and annually, evaluating both individual development and overall program performance, complemented by donor review of the project. These assessments help fine-tune strategies and keep the interventions relevant.

Of course, change on this scale isn’t without hurdles. Significant risks and challenges emerged during implementation:

- Lack of community awareness: This makes it more time-consuming to prepare beneficiaries for available services.

- Inadequate transportation facilities: This makes it difficult to reach beneficiaries in remote areas on time.

- Shortage of human resource: This is a significant challenge within the districts.

- Beneficiary reluctance to relocate: Many beneficiaries are unwilling to relocate for job opportunities due to homesickness.

The team is tackling these challenges head-on—through increased community participation in the planning, implementation, and evaluation of the project. As a community-based initiative, they utilized locally available resources. Parents, volunteers, Self-Help Groups (SHGs), and facilitators were prepared and empowered to sustain field activities. Virtual meetings and sessions were conducted to effectively engage with the community. These strategies have fostered resilience and ownership, reflecting a "for the people, by the people" approach.

Sustainability and the Crucial Role of Government

The model is built for scale and sustainability. Its roots trace back to the successful pilot in Chitradurga, where the project was formally handed over to local government bodies and PwD Federations—a powerful example of local ownership in action. In Yadgir and Raichur, Primary Health Centers and panchayats are beginning to continue services independently—ensuring continuity beyond the life of the project. For instance, CBR centers established by APD are now continuing by the District Disability Rehabilitation Centres (DDRC), the District Disabled Welfare Office (DDWO), and DPOs in Chitradurga, serving as a concrete example of local ownership in action. Government departments, DPOs, and Primary Health Centers are actively continuing project activities.

Crucially, the model is cost-effective. At just Rs. 3,000 per beneficiary per year, it provides a comprehensive approach of providing services in terms of health, rehabilitation, assistive adaptive devices, education, livelihood, accessibility, entitlement, capacity building, awareness, and facilitating self-help groups. The model is cost-effective due to its "depth and saturation model and transdisciplinary staffing model starting from panchayat level to district level."

The government is a key partner in ensuring the project’s scale and long-term systemic change. APD has informal partnerships—established through letter correspondence—with local NGOs, medical colleges, government departments, and local Panchayati Raj Institutions. The government's Department for the Empowerment of Persons with Disabilities, RBSK, Samagra Shikshana Abhiyan, health insurance, and NRLM schemes are leveraged to connect PwDs to entitlements and services. The government also has Urban Rehabilitation Workers (URWs) in urban wards and Village Rehabilitation Workers (VRWs) in rural panchayats whose role is to work for and support the welfare of the disabled.

Expectations from the government include: strengthening the integration of disability-focused services within mainstream systems—like inclusive education in government schools, therapy and rehabilitation through PHCs, and accessible public infrastructure. APD also expects District Rehabilitation Centers (DRC) with all facilities to be established at the earliest. Crucially, they advocate for the timely and purposeful utilization of the 5% reserved budget for PwDs. Furthermore, expectations include: allocating dedicated budgets for disability inclusion, supporting local DPO federations, and ensuring representation of persons with disabilities in planning and monitoring bodies. This collaboration is crucial for institutionalizing successful models and ensuring continuity through government ownership. An inspiring example is Mr. Tayyappa, a beneficiary who, after receiving training, worked as a fellow in the project earning an honorarium of Rs. 5000/-. He was well known in the government department due to his involvement in the RPD task force and Taluk federation. Now he has joined as a VRW in his own gram panchayat, earning more and working for his own gram panchayat, achieving complete independence.

Lighting the Way Forward: Why CSR in Disability Needs to Move from Charity to Strategy

Lighting the Way Forward: Why CSR in Disability Needs to Move from Charity to Strategy

With the third and final year of implementation underway, APD is already looking ahead. The success in Yadgir and Raichur is informing strategic plans to expand the model to additional districts in Karnataka (Kalaburagi, Dharwad, Bangalore Rural) and Kolhapur district of Maharashtra. These expansions will incorporate contextual adaptations based on community feedback and local needs, ensuring the model remains available, accessible, affordable, acceptable, and adaptable, reaching the last mile and leaving no one behind. APD notes that in the 7 to 50 years age group, disability rates are particularly high, necessitating a strong focus on early intervention, education, and livelihood support to ensure this crucial age group's needs are addressed, thereby securing the old age group as well. The pilots in these aspirational districts will help create a district disability management model that can be replicated.

This project is not just a service delivery model—it’s a systems change intervention, profoundly illustrating why CSR in disability needs to move from charity to strategy.

- From Isolated Acts to Integrated Impact: Rather than fragmented interventions, the LCA integrates various services across a person's lifespan and connects them to existing government and community structures. This strategic integration multiplies impact and fosters long-term sustainability.

- From "Helping" to "Empowering": The model empowers PwDs and their families to become agents of their own change, fostering self-reliance and dignity. This shifts the dynamic from passive recipients of aid to active participants in their development and community leadership.

- Cost-Efficiency and Scalability: The model's cost-effectiveness (Rs. 3,000 per beneficiary per year for a comprehensive suite of services) demonstrates that strategic, integrated interventions can be highly efficient and scalable, offering a compelling return on investment for CSR partners.

As Dr. N. S. Senthil Kumar consistently emphasizes, "CSR in disability needs to move from charity to strategy." The Lifecycle Approach exemplifies how systemic impact can be achieved by building disability inclusion directly into rural development programs. It's a model where charity gives way to strategy, and where every rupee invested creates ripples of dignity, equity, and transformation. For Yadgir and Raichur, the journey is just beginning—but the path is lit with purpose.

"In these communities, disability often meant invisibility," says Dr. N. S. Senthil Kumar, the lead architect of the program and CEO of APD India. "Families were unaware of services, stigma ran deep, and there was no systemic support. We wanted to change that—from the inside out.”

"In these communities, disability often meant invisibility," says Dr. N. S. Senthil Kumar, the lead architect of the program and CEO of APD India. "Families were unaware of services, stigma ran deep, and there was no systemic support. We wanted to change that—from the inside out.” The LCA model treats inclusion not as a one-time intervention but as a continuous journey, supporting PwDs across four interconnected life stages: early childhood, school-age, working age, and old age. Each phase is marked by targeted services—ranging from home-based physiotherapy, inclusive education, assistive devices, and skill development to access to entitlements and livelihood support. The rehabilitation strategy is broad and inclusive; it goes beyond physical care, encompassing social inclusion, education, and economic empowerment.

The LCA model treats inclusion not as a one-time intervention but as a continuous journey, supporting PwDs across four interconnected life stages: early childhood, school-age, working age, and old age. Each phase is marked by targeted services—ranging from home-based physiotherapy, inclusive education, assistive devices, and skill development to access to entitlements and livelihood support. The rehabilitation strategy is broad and inclusive; it goes beyond physical care, encompassing social inclusion, education, and economic empowerment. Livelihoods and Empowerment: 60+ persons with disabilities have received seed funding and business mentoring, creating pathways to sustainable livelihoods. In Raichur, 200 youth were placed in jobs, 50 supported in self-employment, and 124 linked with MGNREGA job cards. In Yadgir, 13,562 PwDs accessed various social security schemes, and overall, 9,720 beneficiaries gained access to various social security schemes. Over 45,000 rehabilitation services have been delivered to individuals in Raichur.

Livelihoods and Empowerment: 60+ persons with disabilities have received seed funding and business mentoring, creating pathways to sustainable livelihoods. In Raichur, 200 youth were placed in jobs, 50 supported in self-employment, and 124 linked with MGNREGA job cards. In Yadgir, 13,562 PwDs accessed various social security schemes, and overall, 9,720 beneficiaries gained access to various social security schemes. Over 45,000 rehabilitation services have been delivered to individuals in Raichur. Lighting the Way Forward: Why CSR in Disability Needs to Move from Charity to Strategy

Lighting the Way Forward: Why CSR in Disability Needs to Move from Charity to Strategy

.jpg)