In the sphere of rural development, the convergence of diverse initiatives has long been a topic of critical importance. The need for seamless integration and inclusive approaches has become increasingly apparent, shedding light on the intricate dynamics at play. As we strive to uplift rural areas, it is crucial to foster an environment where everyone's input is valued, ensuring that no voice goes unheard. This democratic approach not only encourages community engagement but also fosters a sense of ownership and empowerment among all individuals involved in the development process. As various programs endeavour to address the multifaceted challenges within rural communities, the significance of design as a catalyst for transformative change has come to the forefront.

In the sphere of rural development, the convergence of diverse initiatives has long been a topic of critical importance. The need for seamless integration and inclusive approaches has become increasingly apparent, shedding light on the intricate dynamics at play. As we strive to uplift rural areas, it is crucial to foster an environment where everyone's input is valued, ensuring that no voice goes unheard. This democratic approach not only encourages community engagement but also fosters a sense of ownership and empowerment among all individuals involved in the development process. As various programs endeavour to address the multifaceted challenges within rural communities, the significance of design as a catalyst for transformative change has come to the forefront.

André Nogueira, CEO of Leap Design, an initiative of Transform Rural India (TRI), amplifies this narrative, leveraging his extensive expertise to underscore the pivotal role of design in shaping the trajectory of rural development. Recognized for his innovative work in utilizing design methodologies for societal well-being, he also serves as the Co-Founder and Deputy Director of the Design Laboratory at Harvard, highlighting his significant contributions to cross-sectorial partnerships. With a rich background in spearheading transformative initiatives in the US and Brazil, Nogueira brings valuable practical knowledge to the discourse on inclusive development strategies. Notably, his global recognition includes the prestigious 40 under 40 Public Health Catalyst Awards, further emphasizing his commitment to fostering design capacity within organizations.

In this captivating article, Nogueira delves into the intricate relationship between design and rural development in India. Addressing the interconnected nature of development initiatives, he highlights pivotal issues such as the challenges posed by scalability and the need to respect the diversity of contexts within rural India. Through thought-provoking inquiries, Nogueira aims to stimulate discourse and advocate for adaptable solutions that can drive meaningful change within the development sector.

Explore the complete article below for a comprehensive understanding of the intricate dynamics shaping rural development strategies:

For decades, many organizations have worked hard to help solve specific issues in rural areas. Pop-up clinics, food stamps, irrigation incentives, and micro-loan mechanisms are a few examples of many creative solutions implemented by organizations across sectors in India, including government agencies, foundations, private corporations, and individual donors. Each with its network of agents and agenda, these organizations evolved to act autonomously while often aiming at serving the same population in the same context and at the same time.

Although this creative set of specific solutions has significantly improved the lives of millions, the lack of strategic interconnectedness between available offerings - and the organizations behind- them is now placing the onus on rural dwellers to navigate complex journeys when trying to learn about available schemes, apply for them, and optimize the benefits to improve their overall well-being. How can farmers link micro-loan mechanisms, irrigation and solar-panel incentives, and seed distribution schemes offered by different organizations to grow their businesses? How can they plan business growth and land investment for crop diversification? How can villagers choose which health screening service they should attend? Without the capability to effectively connect disjointed programs into more integrated systems that improve people's choice-making processes daily, organizations will continue to grow and evolve their efforts at the expense of increasing complexity in village life.

Recognizing the need to shift from point solutions to enabling new choice-making conditions, the Transform Rural India has launched the India Rural Colloquy, an annual event structured around discussions on social transformation. The colloquy was conceptualized to mobilize more focused policies and investments for equitable development in rural villages, and it involves global thought leaders, Indian practitioners, community members, policymakers, and senior executives in India and elsewhere. In 2023, the third version of this colloquy was structured around the theme of Rural Renaissance and had three parts. The first occurred in Ranchi and Bhopal on July 18.The second happened in Raipur on July 22. Finally, the last part occurred in Delhi between August 1 and 8.

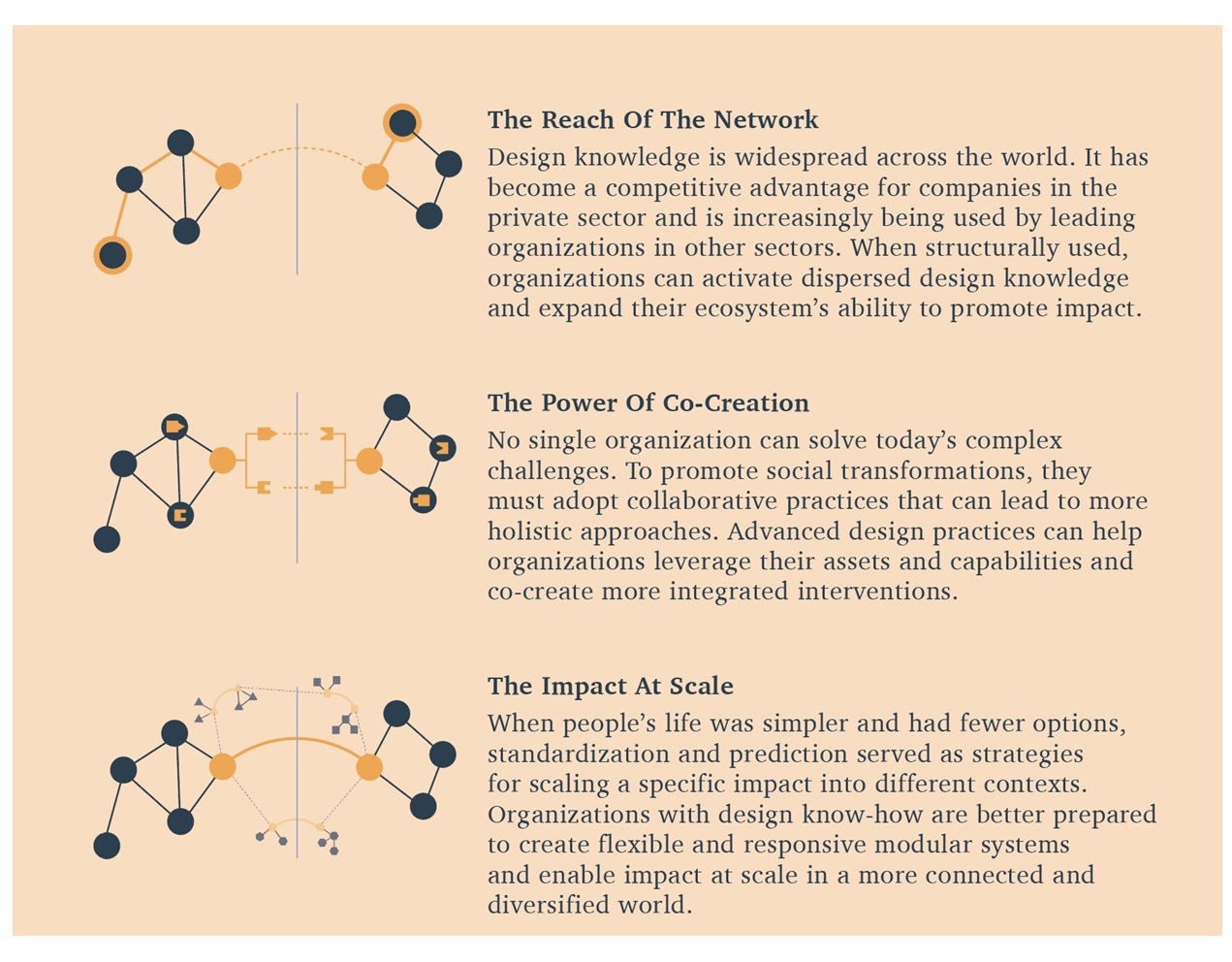

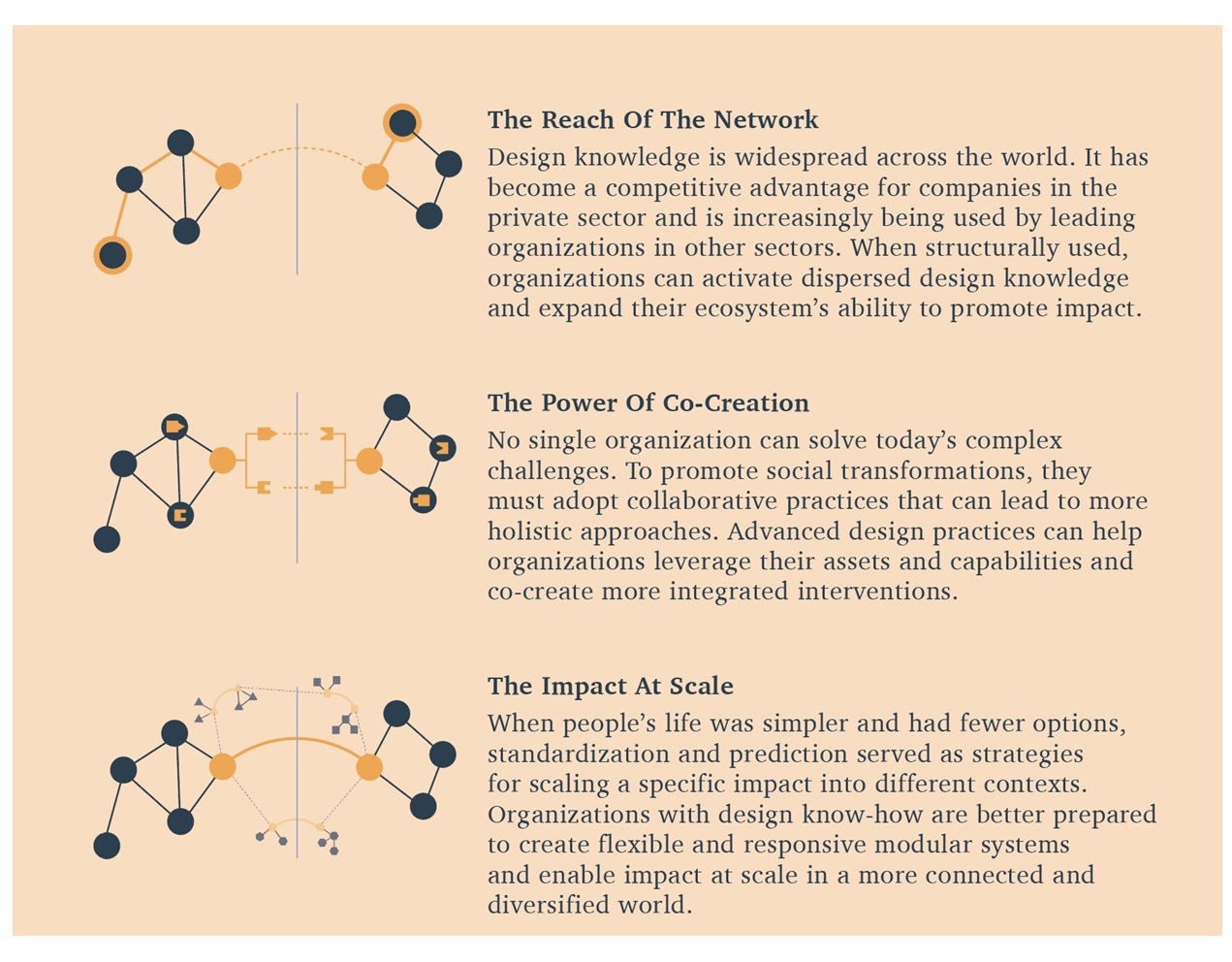

Last year was the first time the colloquy invited design into these discussions. I had the privilege to moderate an online conversation on Design For Better World: Global Well-Being In Post-Industrial Society, involving Patrick Whitney, Sam Pitroda, Anirban Ghose, and Rajni Bakshi,. This year, I was honored to expand on the contributions and limitations concerning design. On August 2nd, a selected group of leaders from across sectors got together at the Sanskrit Kendra, Delhi, to explore how design can help expand and accelerate leap changes as Indian organizations work towards improving the well-being of the people they serve and the ecosystems in which they live. This time, the convening was hybrid and benefited from the participation of Sarah Szanton, Carlos Teixeira, Anish Kumar, Sonia Manchanda, Ayush Chauhan, and Patrick Whitney. Together, we dove deeper into three systems-level concepts related to how design knowledge, practice, and know-how can contribute to shifting conditions in the development sector: the reach of the network, the power of co-creation, and the impact at scale.

Many topics surfaced during these exchanges relate to spaces where design value can contribute robustly. All are documented in the online recording and must receive proper attention. But two were deeply and furiously discussed: decision-making power and the paradox of scalability and diversity.

Power in decision-making processes

Decisions made throughout development initiatives inherently sustain a projected vision for the future that will, invariably, be shaped by the interactions among stakeholders involved in the decision-making process. The conventional decisions underlying activities of framing and implementing development schemes often happen through formalized channels and formats within which funders, private organizations, and government agencies are attributed the legal authority and power to decide what problems to prioritize, what features and offerings to include in their schemes, and what additional systems support, such as access to loans, might be needed. Unsurprisingly, different stakeholders will present different visions - and related expectations - about that future. Those with greater power within the ecosystem will decide on pathways forward, even if they go against priorities of local bodies.

Such a condition reinforces any development initiative's social, political, and cultural nature: Who gets to frame the problems, determine priorities, and conduct impact assessments? What forms of authority are given power? Which stakeholders lead? Which are included and which are excluded?

In the past decades, the ever-increasing algorithmic complexities underlying these and other decision-making processes have become an object of interest and engagement for many leaders inviting designers into complex development challenges. They have realized the power asymmetry between the makers and users of development schemes creates a knowledge gap concerning what schemes should be made and why they would create value for village life.

In this context, these leaders have relied heavily on human-centered design approaches to better understand villagers' daily life choice-making processes, but there remain greater opportunities to amplify the voices of rural dwellers and local stakeholders in decision-making processes that condition their options for choice-making.

Paradox of scalability and diversity

How are you going to achieve scale? That is a fundamental question that most development agents are asked at some point in their complex journeys. While the context within which this question emerges varies, it is usually structured around a common expectation that a successful impact can be standardized to be reproduced elsewhere. In this model, scalability efforts involve development agents working with influential stakeholders (e.g., government agents, foundations, and corporate partners) to grow the size and reach of their scheme as a path to increase the number of people involved in and benefiting from a successful endeavor.

Many researchers and development agents, however, have emphasized that most efforts within this scalability model must be contested as they overlook the contextual variations. In rural India, various daily life activities, experienced as expressions of culture and related individual and collective identities, engender behavioral and technical factors that cannot be decoupled from place-based, historical experiences, different knowledge systems, existing power asymmetries, and institutional politics. For example, extremist violence due to political frictionshas remained an impediment to the success ofgovernment-led development efforts, including the “Digital Governance”. This program has made internet a necessary condition for villagers to access social-protection programs, includingminimum work guarantees and public food distribution. Such a condition illustrates how difficult can be for successful solutions in one geography or community to succeed elsewhere.

Of course, this doesn't mean every development initiative should start from scratch.However, it does mean that scalability attempts, especially those dominated by Western worldviews, principles, and values around centralization, standardization, and predictability, have shown their limitations to the sector. Hence, the efforts of bringing design, emphasizing the need for adopting of more pliant and responsive ways of working. Sarah Szanton’sundertake of bringing design into the Community Aging in Place – Advancing Better Living for Elders (CAPABLE) framework and later embedding design as a capability of the John Hopkins School of Nursing research infrastructure are testaments of such shift. Sarah is one of several ambitious leadersleveraging design to shape more flexible and responsivecare systems rather than trying to come up with pointed, silver-bullet solutions that become standards for tackling similar problems in different realities.

Forging Pathways Together

The intellectual contributions, examples, thoughtful questions, and discussions throughout the Rural Colloquy were a powerful testimony that Indian leaders are ready to build upon past accomplishments and ensure an even brighter future for rural areas and beyond. Rather than reinforcing isolated efforts, participants recognized leaders must invest in journeys that can expand their ability to work at the intersection of issues, strategically bridging their knowledge to create more holistic interventions.

The leaders in the room and their networks know this is a transformational moment that requires initiatives that are audacious intheir purpose and exploratory at their core. Their urgency is apparent: a call for action integrating diverse knowledge systems with design, including those from different disciplines involved in development efforts and local context. The opportunity is also clear: exploring new ways for leaders across sectors to work with a broader and more inclusive range of stakeholders willing to think big, start small, and translate their bold visions into meaningful impact at the appropriate scale. They are ready for a leap change. But there remains a critical question.

Are designers ready?

While many designers seem genuinely interested in tackling such complexity, several leaders at the event recognized the Achilles heel of the field: the lack of a body of knowledge that supports designers in addressing the ambiguity inherent in development challenges. As Patrick Whitney alluded, because design knowledge is relatively informal, designers can find it difficult to link their contributions to other ways of working and knowledge systems supporting development initiatives. For example, when engaging in such a complex decision-making context, designers inevitably lack proper conceptual models to deal with ideological issues and debates surrounding the dynamics of rural living. Also, they often encounter funders, partners, and local stakeholders who are not necessarily familiar with design approaches. Even when the value of utilizing specific methods is realized, such as gaining unique behavioral insights through user and field observations, the organizations that have been able to internalize them sustainably are almost inexistent, especially if the assessment considers work at the local, regional, and national levels.

Based on his 20+ years of experience in leading systems change across the globe, including in India, Carlos Teixeira shared how critical it is to recognize the boundaries of design contribution in the context of development initiatives. For him, understanding the value created after designers' involvement is neither simple nor uncontested, and it must be attributed at the intersection of multiple systems and within the broader social, political, and cultural context shaping its decision-making process. Thoughtfully, Sonia Manchanda and Ayush Chauhan expanded this view through real-world examples that demonstrated how, too often, the motivations and priorities considered in design approaches do not land themselves on those of the representatives of funders and government agencies. So much so that many designers claim it is more effective to create new systems that make existing ones obsolete than working through partnering with local organizations.

As well-equipped to deal with complexity within a specific organizational context as it may be, the design field has yet to adequately engage with complex social challenges. If designers are to continue to help promote leap changes in the development sector, the field will have to develop new frameworks and methods to better welcome diverse and often conflicting viewpoints around the purpose of making change. In doing so, they will be better prepared to help multiple stakeholders work together when confronting systemic complexity, including those responsible for making new schemes with those interested in using these schemes to improve their overall well-being.Importantly, these advancements must not be made in the conventional fashion model in which the field's knowledge, practice, and know-how have evolved. Instead, they must be connected to reliable theories, with evidence that they are effective in practice, easily understood by others, and expandable through solution-oriented research.

Where to being?

Although this piece communicatesa shared interestamong Indian leaders to leverage design knowledge, practices, and know-how for creating new development directions that go against norms and beliefs historically established in the sector, the intent is not to use existing approaches to predict the best way forward and then plan with precision. Instead, it is to work together to identify seismic forces shaping development outcomes -such as fragmentation in existing schemes and disconnection from villagers’ daily experiences andbuild leadership capacity to promote leap changes by design.

Transformative changes in the scope, scale, and speedof development challenges will be upon India faster than current leaders expect. The scope is already broad, extending diversity in daily lives into new governing structures and scalability models. The scale we all know is huge and cuts across sectors, geographies, and systems levels. And we must act fast as it is taking too long to make significant improvement in the lives of the 200+ millions of people experiencing poverty every day and the ecosystems within which we all live in.

As the recent G20 New Delhi Leaders’ Declaration, states, “together we have an opportunity to build a better future”. This means not only finding ways to bridge siloed endeavors that have led to myopic interventions to create more holistic approaches, but also making sure such efforts result in new systems today that will improve the well-being of an ever-diversifying global population and, of course, the planet.The world needs audacious leadership to create such approaches and build such systems. India can help lead the way.

In the sphere of rural development, the convergence of diverse initiatives has long been a topic of critical importance. The need for seamless integration and inclusive approaches has become increasingly apparent, shedding light on the intricate dynamics at play. As we strive to uplift rural areas, it is crucial to foster an environment where everyone's input is valued, ensuring that no voice goes unheard. This democratic approach not only encourages community engagement but also fosters a sense of ownership and empowerment among all individuals involved in the development process. As various programs endeavour to address the multifaceted challenges within rural communities, the significance of design as a catalyst for transformative change has come to the forefront.

In the sphere of rural development, the convergence of diverse initiatives has long been a topic of critical importance. The need for seamless integration and inclusive approaches has become increasingly apparent, shedding light on the intricate dynamics at play. As we strive to uplift rural areas, it is crucial to foster an environment where everyone's input is valued, ensuring that no voice goes unheard. This democratic approach not only encourages community engagement but also fosters a sense of ownership and empowerment among all individuals involved in the development process. As various programs endeavour to address the multifaceted challenges within rural communities, the significance of design as a catalyst for transformative change has come to the forefront.

.jpg)

.jpg)